Pedagogical series: your new testimonial series!

Join live sessions featuring real use cases shared by our users.

5 myths on education

05.07.2024 • 3 minutes

This article highlights 5 significant neuromyths in education, challenging misconceptions with scientific evidence.

This article is based on the book written by Pedro De Bruyckere, Paul A. Kirschner and Casper Hulshof, "Urban Myths about Learning and Education" (2015) and its direct sequel "More Urban Myths About Learning and Education" (2019).

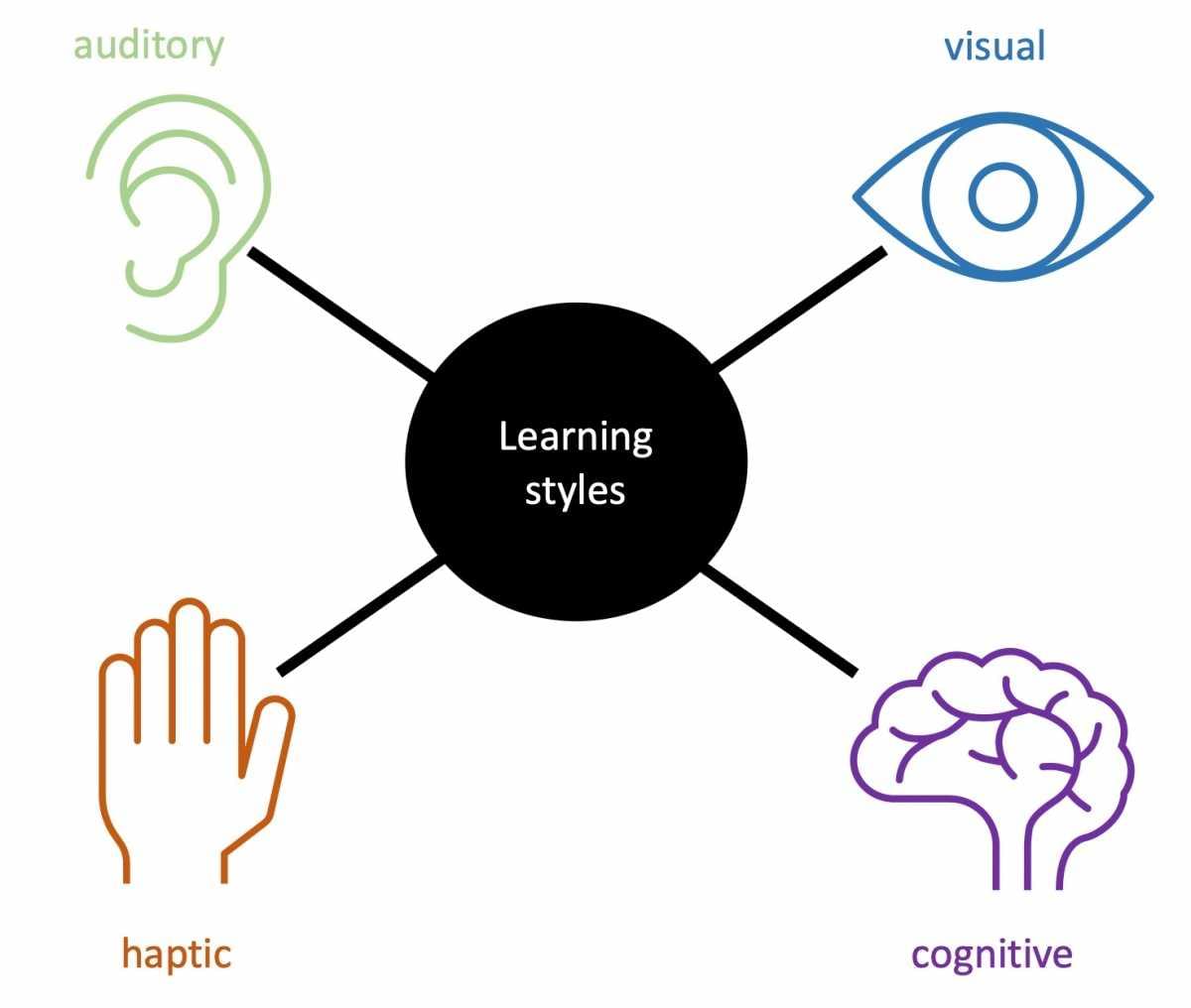

1. People don’t show specific learning styles and don’t fit predefined personality types.

To state that people have a preferred learning strategy is a trivial observation, not groundbreaking. However:

- What you prefer is not necessarily what is good for you. No instructional benefit of a particular learning technique was ever observed for people declaring that it was their primary choice. Preferred instructional methods can even be unproductive.

- Most so-called learning styles correspond to one or more theories of personality types. Despite the huge (and lucrative) success of this idea in the private sector, the claim that people cluster in distinct groups has inadequate support.

This does not mean that some people won’t be slightly better at remembering written words, for example. But certainly nobody has a problem learning written words, pathologies aside.

Does that mean that all students are equal and should be treated in the same way? Again, no: what research states is simply that learning styles is not a theory of instruction and should be ignored for that purpose.

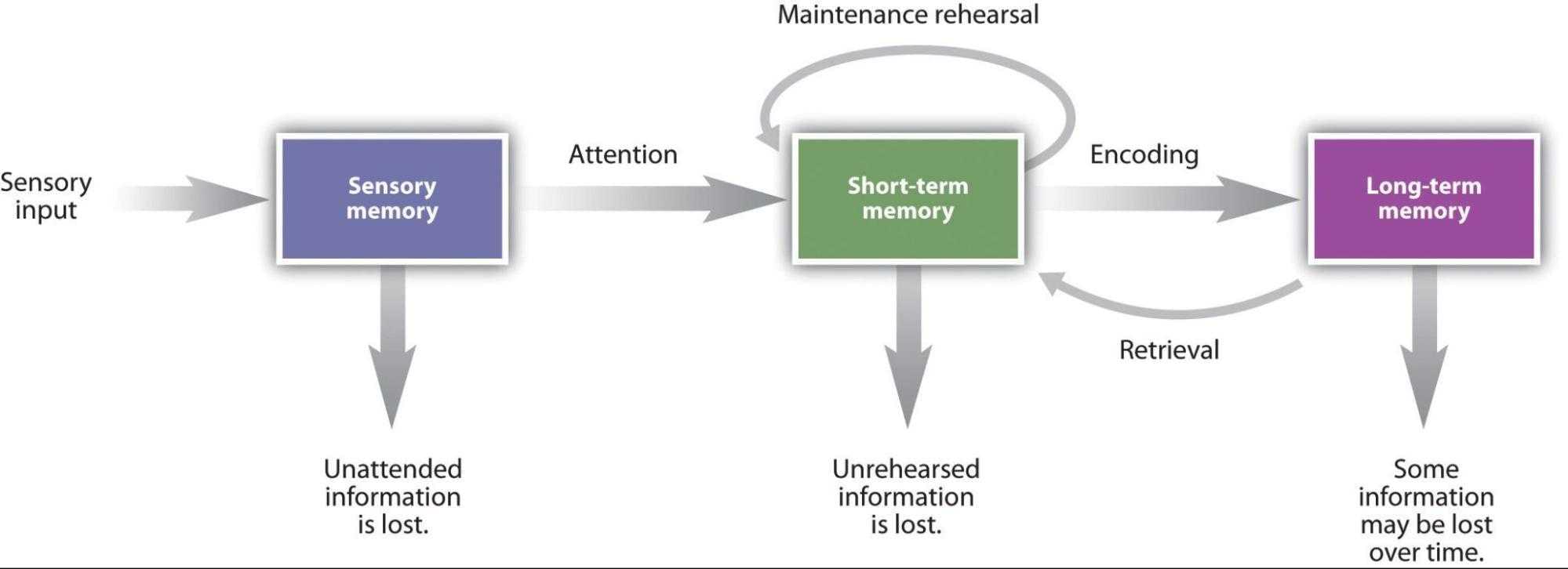

2. Our memory does not store a perfect record of our experience

Remembering what the teacher said or what was learned in the past is an essential ingredient of education. Memory is quite a complex mechanism. According to most theories of cognition, memory is divided into:

- Sensory memory: when external stimuli reach one of our senses. Information is already heavily filtered at this stage because we deliberately or unconsciously ignore incoming stimuli.

- Short-term or working memory: is very limited in time and size (30 seconds for about seven elements). It helps organise and compare information.

- Long-term memory helps give meaning to knowledge. It probably has an unlimited storage capacity and is a permanent record of what one truly learns.

Whether adults claiming to have “photographic memory” have ever been rigorouslytested is a very controversial subject. In general, human memory is full of flaws:

- Our minds are not empty jars waiting to be filled by knowledge provided by experts. - Memory reconstructs information according to what fits our schemas.

- Perception is distorted by our biases. Our knowledge determines our experience, not the other way around.

Memory is personal, and changes over time. We are what we forget.

3. Students are not brain-dead during lessons and lectures.

One of the urban legends spread even by award-winning professors is that students’ brain activity during traditional lectures is the same as when watching TV: plain dead. It turns out, the study that is cited did not measure brain activity, but rather electrodermal activity. Even worse, this measurement was performed on a single student, invalidating any meaningful conclusion on a general population.

That being said, lectures play a key role in education, and are sometimes very effective. Most of the time however, they cause the audience’s attention to drift. Low-performing students (that is, the ones needing the benefits of education the most) are unfortunately among the victims of this effect. Keeping students interested and engaged is maybe the greatest challenge for teachers.

Quizzes are known to increase the effectiveness of lectures, as they involve well-known mechanisms such as the testing effect and the retrieval practice. Quizzes also close the performance gap by 50% between students from lower and higher socio-economic backgrounds.

4. More lecture time does not automatically lead to more learning.

Sometimes simplistic ideas are applied to education and become official recommendations. Policy makers may base their decisions on indicators that fail to identify causality. In this case, correlations between learning and hours spent at school certainly exist, but no other connection is known. When Mexico and Germany increased the number of lesson hours, the outcome was underwhelming:

The learning gain was negligible. The divide from students with different socio-economic backgrounds deepened.

Why did that happen? In short, besides the obvious consideration that what happens during the additional hours is part of the equation, increasing the class time does not benefit everyone equally. “Richer” students benefit from their additional background, stimuli and help at home. The only way to compensate for this gap seems to allocate additional resources to the students that specifically need it.

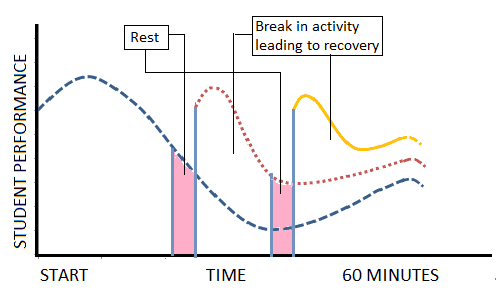

Additionally, we stress once again that time away from school and studying is beneficial to the learning process. In fact,

- regular breaks at school,

- expansive spaced practice and repetition,

- physical activity during one’s free time,

- getting enough sleep,

all lead to better learning.

5. Teachers do make a difference, but they’re not the only factor.

The factors that do or do not contribute to learning are especially hard to investigate, all factors affect each other in so many different ways. But claiming that the teacher has the largest impact on the students (30% being even an overestimation) is certainly a myth.

There are in fact too many things out of a teacher’s control:

- the states’ educational policies, the genetic make-up of students, their home situations.

However this is no excuse for the teachers to lose hope or not to keep doing their best. Their impact is certainly positive.

Expert teachers do make a difference when they are able to:

- Set appropriate goals for the students to motivate them,

- Have in-depth knowledge of their domain, and how people learn, providing a well-organised course and linking the content to other disciplines, or students’ prior knowledge.

- Monitor more demanding students and give appropriate feedback.

Writer

The Wooclap team

Make learning awesome & effective

Subject

A monthly summary of our product updates and our latest published content, directly in your inbox.